. . .

The limits of human adaptability

Scientists and other observers have become alarmed about the increasing frequency of extreme heat paired with high humidity.

In the Middle East, Asaluyeh, Iran, recorded an extremely dangerous maximum wet-bulb temperature of 92.7 F (33.7 C) on July 16, 2023 – above our measured upper limit of human adaptability to humid heat. India and Pakistan have both come close, as well.

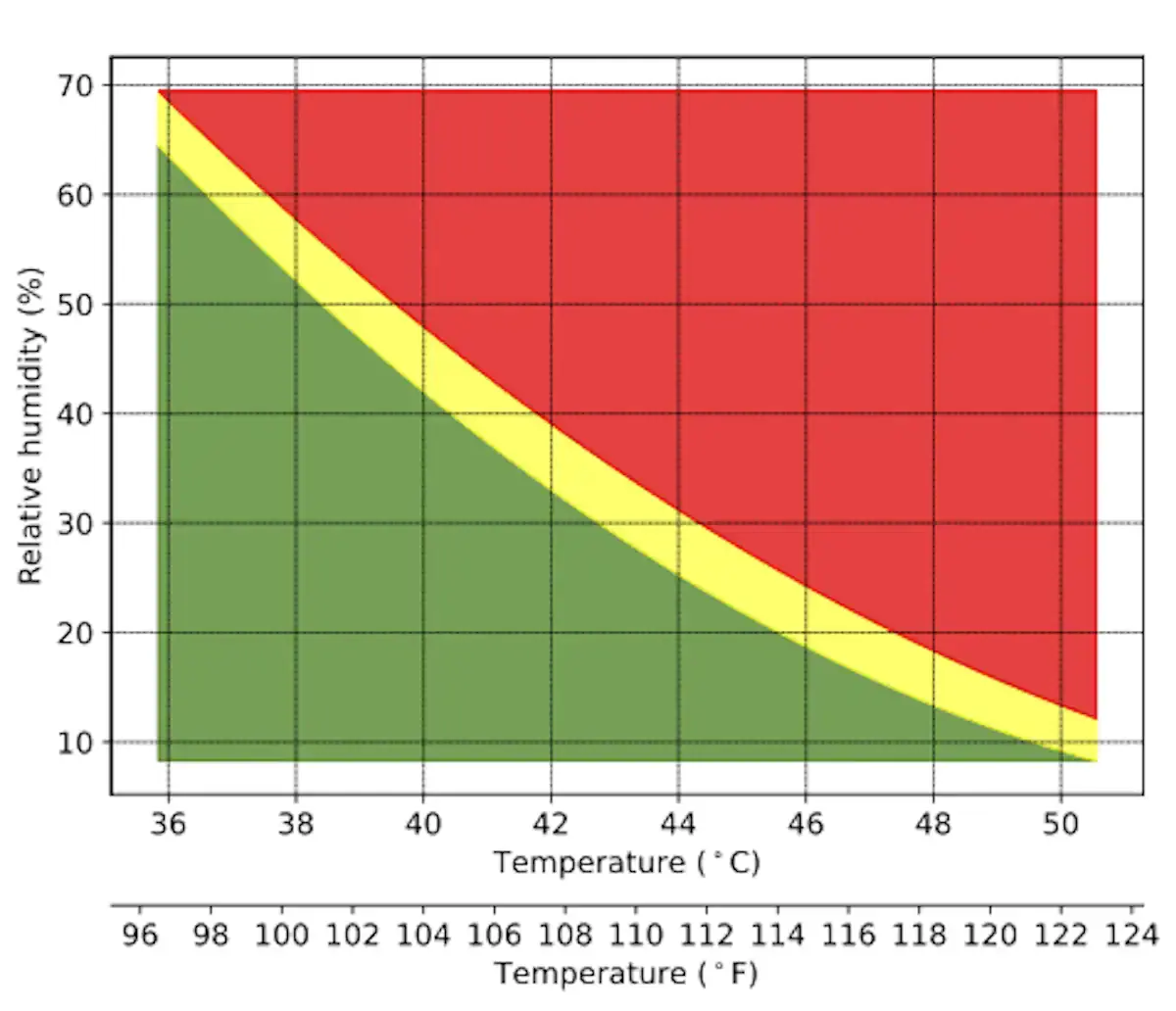

People often point to a study published in 2010 that theorized that a wet-bulb temperature of 95 F (35 C) – equal to a temperature of 95 F at 100% humidity, or 115 F at 50% humidity – would be the upper limit of safety, beyond which the human body can no longer cool itself by evaporating sweat from the surface of the body to maintain a stable body core temperature.

It was not until recently that this limit was tested on humans in laboratory settings. The results of these tests show an even greater cause for concern.

. . .

This temperature / humidity chart from their article is quite alarming. Seems that is only a matter of time before lethal heat / humidity combinations begin to take place in urban centres.

Adequate hydration is clearly a must and maintinating good physical and cardiovascular health are going to help, but I wonder whether some form of dehumidification specifically, rather than just cooling, could also aid survival?

but I wonder whether some form of dehumidification specifically, rather than just cooling, could also aid survival?

It’s a lot cheaper to just become morlocks and sleep underground during the day and emerge on the surface at night.

Solar/wind power and heat pumps and personal air conditioners are a lot more costly than LED lights to work at night.

Or worse, mass migration north/south out of the hot and humid equatorial regions.

We’re heading towards the Dune universe aren’t we?

but I wonder whether some form of dehumidification specifically, rather than just cooling, could also aid survival?

The issue is that in general, dehumidification is energy intensive, just as cooling is. In fact, one of the best ways to dehumidify air is to cool it down. Other non-mechanical solutions, like chemical solutions (e.g., dry hygroscopic material with large surface area) don’t have an energy cost during their use, but they have an energy cost in their production and renewal. For example, to dry the hygroscopic material back out to recycle it and re-use it, you must supply a lot of heat energy.

I would be interested in an energy consumption comparison though, between: cooling air to keep it under the red area of the curve; dehumidifying air to keep it under the red area of the curve; and some combination of the two (as most air conditioning units do). It may be the case that dehumidifying is less energy intensive.

Yeah; I have no idea as to the energy requirements.

It won’t be possible to dry out any dessicant in the sun because the air saturation issue will nix that in the same way it renders sweating ineffective.

Am I taking crazy pills? Why did everyone suddenly start saying that records “fall”??