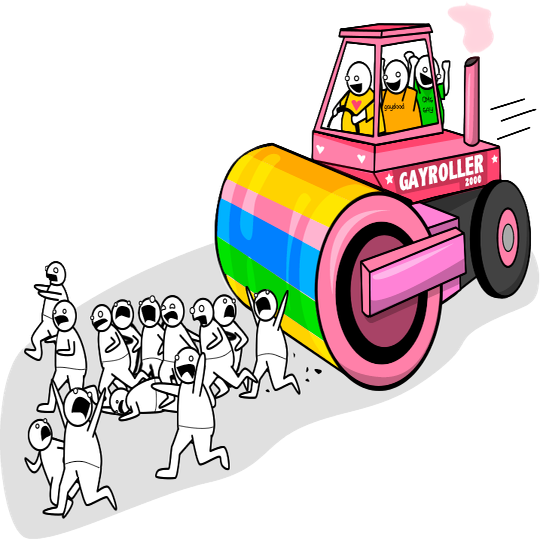

The rainbow flag or pride flag is a symbol of LGBT pride and LGBT social movements. The colors reflect the diversity of the LGBT community and the spectrum of human sexuality and gender. Using a rainbow flag as a symbol of LGBT pride began in San Francisco, California, but eventually became common at LGBT rights events worldwide.

Originally devised by the artists Gilbert Baker, Lynn Segerblom, James McNamara and other activists, the design underwent several revisions after its debut in 1978, and continues to inspire variations. Although Baker’s original rainbow flag had eight colors, from 1979 to the present day the most common variant consists of six stripes: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. The flag is typically displayed horizontally, with the red stripe on top, as it would be in a natural rainbow.

LGBT people and allies currently use rainbow flags and many rainbow-themed items and color schemes as an outward symbol of their identity or support. There are derivations of the rainbow flag that are used to focus attention on specific causes or groups within the community (e.g. transgender people, fighting the AIDS epidemic, inclusion of LGBT people of color). In addition to the rainbow, many other flags and symbols are used to communicate specific identities within the LGBT community.

Variations:

Original Gilbert Baker Design

Inspired by the lyrics of Judy Garland’s Over the Rainbow, and the designs used by other social movements such as black civil rights groups from the 1960s, the Rainbow Flag was created. Baker hand-dyed and hand sewed this flag which flew at the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day in June 1978.

Seven-color version due to unavailability of pink fabric

Following the assassination of Harvey Milk in 1978, many people and organisations adopted the Pride flag that he helped to introduce to the community. The demand was so great for a rainbow striped flag, it was impossible for the 8-stripe design to be made in large quantities. Both Paramount and Baker struggled to obtain the hot pink fabric and so began manufacturing a 7-stripe version.

Traditional Gay Pride Flag

In 1979 the design was amended again. The community finalised this six-colour version and this is now the most familiar and recognisable design for the LGBT flag. Numerous complications over the odd number of stripes, including the desire to split the flag to decorate Pride parades, meant that one colour had to be dropped.

The turquoise and indigo stripes were combined to create a royal blue stripe and it was agreed that the flag should typically be flown horizontally, with red at the top, as it would be in a natural rainbow. This design continued to increase in popularity around the world, being a focal point of landmark decisions such as John Stout fighting for his right to fly the flag from his apartment balcony in 1989.

Progress Pride Flag

In June 2018, designer and activist Daniel Quasar released an updated version of the Pride flag. Combining the new elements of the Philadelphia design and the Transgender flag to bring focus on further inclusion and progress. This new flag added a chevron to the hoist of the traditional 6-colour flag which represents marginalised LGBTQ+ communities of colour, those living with HIV/AIDS and those who’ve been lost, and trans and non-binary persons.

This design went viral and was quickly adopted by people and pride parades across the world. The arrow of the chevron points to the right to show forward movement, while being on the left edge shows that progress still needs to be made for full equality, especially for the communities the chevron represents.

Intersex Inclusive Progress Pride Flag

In 2021, Valentino Vecchietti of Intersex Equality Rights UK adapted the Pride Progress flag design to incorporate the intersex flag, creating the Intersex-Inclusive Pride flag 2021.

The intersex community uses the colours purple and yellow as an intentional counterpoint to blue and pink, which have traditionally been seen as binary, gendered colours. The symbol of the circle represents the concept of being unbroken and being whole, symbolising the right of Intersex people to make decisions about their own bodies.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- 📀 Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 🔥 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- ⚔ Come talk in the New Weekly PoC thread

- ✨ Talk with fellow Trans comrades in the New Weekly Trans thread

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

feel like the mechs in matrix 3 could have had a little protection for the driver. seems like it might have been a good idea

The robots target the weak point and there are obviously plenty of replacement human pilots. so making the pilot the weak point insures the fastest and easiest “fix” for a downed mech. Any protection would make the mech more likely to be damaged while being disabled. The robots seem to be unable to grasp why humans would choose pain and struggle in exchange for “freedom”. So maybe they don’t understand why people would get in a death machine so they don’t bother breaking the mechs any more than required to kill the human.

The machines also know that they’ll have to fix them… like who built rebuilt Zion every time they reset the program? The machines. They had to clean it up, fill in all their tunnels they dug to get to Zion etc. and the whole thing starts over again

I got the impression that at least some of the machines understood us pretty well. They’re not all uptight dorks like smith. The humans had some machine allies and sympathizers.

I wonder if the squids were people, or drones? Like was each one of them a warrior, or are they dumb robots?

I kinda thought with his position of leading the robot gestapo that Smith was probably one of the better human analysers. But then again he must have been a young program because he didn’t know about the cyclical nature of the war. Now I’m wondering how many of the robots knew about that. Is it like a hard coded secret? “We never tell humans about the cycle”

I feel like the way the squids moved in concert they were all governed by the same AI.

I guess they didn’t have much time to better equip the mechs?

I guess it’s the “you can’t act wearing a helmet” thing. They were pretty unique looking, and that whole scene was just utterly unapologetic rule of cool.

I think the lore-friendly explanation is that the humans left in zion are placed there by the machines after the last Matrix reset. Humans can maintain the technology, but can’t meaningfully improve it because they don’t really understand it. And everything in Zion is designed toward an easy re-invasion by the machines.

The actors wanted their faces to have more screen time.

(I am a champion buzzkiller.)

Love, that one scene was intense for a just-turned-10 year old. I sometimes think my desensitization to violence will come in handy during the Rev, but I dread that day.