No matter how tired you get, no matter how you feel like you can’t possibly do this, somehow you do.

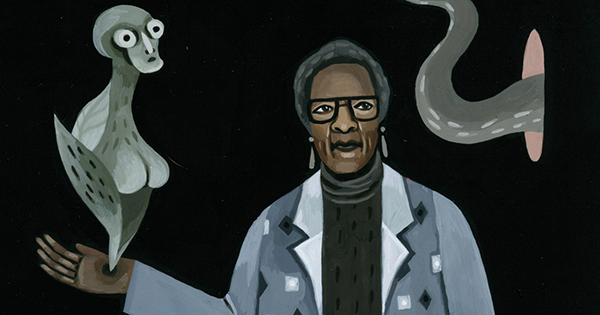

Once, Octavia Butler (June 22, 1947–February 24, 2006) set out to write a memoir. But she found that “it felt too much like stripping in public,” so she abandoned it. Today, all of her autobiographical reflections, all of her overt politics, all of her creative credos come down to us solely through her interviews, now collected in Octavia E. Butler: The Last Interview and Other Conversations (public library).

These conversations are also the reliquary of Butler’s hard-honed wisdom on the craft of writing, which she taught herself and mastered against the odds of her time and place to become one of the most abiding and beloved literary voices of the past century — part prophet, part poet of possibility.

In an interview given just as she was beginning what would become her iconic Parable of the Sower, she offers young writers the pillars of the craft:

"The first, of course, is to read. It’s surprising how many people think they want to be writers but they don’t really like to read books… The second is to write, every day, whether you like it or not. Screw inspiration."More than a decade later, having proven it with her own life, she redoubles her faith in work ethic over inspiration as the central drive of art. An epoch after Tchaikovsky observed that “a self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood” and Camus insisted that “works of art are not born in flashes of inspiration but in a daily fidelity,” Butler exhorts young writers:

"Forget about inspiration, because it’s more likely to be a reason not to write, as in, “I can’t write today because I’m not inspired.” I tell them I used to live next to my landlady and I told everybody she inspired me. And the most valuable characteristic any would-be writer can possibly have is persistence. Just keep at it, keep learning your craft and keep trying." "Forget about talent, whether or not you have any. Because it doesn’t really matter. I mean, I have a relative who is extremely gifted musically, but chooses not to play music for a living. It is her pleasure, but it is not her living. And it could have been. She’s gifted; she’s been doing it ever since she was a small child and everyone has always been impressed with her. On the other hand, I don’t feel that I have any particular literary talent at all. It was what I wanted to do, and I followed what I wanted to do, as opposed to getting a job doing something that would make more money, but it would make me miserable."It was not easy for Butler to follow what she wanted to do. She did have to take terrible job after terrible job. She worked at a hospital laundry. She worked as a telemarketer. (“I have a good phone voice,” she says apologetically. “I am told I have a good phone presence, and I actually sold things to people. I’m very ashamed.”) But all along, she was writing and writing. Looking back on the dogged devotion of those early days, that vital time when the foundations of one’s craft and credo are laid down, she reflects:

I remember another writer and I corresponding, and he had dropped out. I said, “Why haven’t I seen more from you?” He said, “Well, I didn’t make anything on my first three books.” My comment was, “Who makes anything on their first three books?” I remember that the time I quit that laundry job, it was to go to a Worldcon in Phoenix… I decided I was going to try to live as frugally as possible, and at that time you really could live very frugally. My rent was one-hundred dollars a month. So if you were content not to drive, and if you were content to wear the same clothes that you’d been getting along on for a long time… and there were other ways of not spending lots of money. I didn’t eat potatoes for years after that. I decided that I was going to live off the writing, somehow. "No matter how tired you get, no matter how you feel like you can’t possibly do this, somehow you do."When an interviewer relays the apocryphal story of how Bram Stoker spent years producing mediocre writing without anyone’s notice until one day lightning struck him and out came Dracula, Butler immediately refutes this myth of divine inspiration with its dangerous intimation that excellence is the product of circumstance or chance. Having placed at the heart of her Parable of the Talents the question of creative drive, having framed it as a matter of “a sweet and powerful positive obsession,” she insists once again on the immense creative power of simply showing up for the work:

"It’s one of the things that I try to keep young writers from thinking, that you have to wait, that it’s all luck, lightning will strike and then you’ll have a wonderful bestseller. So I think it’s like the old idea that fortune favors the prepared mind. If you’ve developed the habit of paying attention to the things that happen around you and to you, then, yeah, you’ll get hit by lightning."

@MHowell asɛnka nni ho! Great read and good points, especially this one:

That tug is the old call of the storyteller - that there is something vital in your words, needed by someone, somewhere, and that alone makes the tale worthwhile to tell.