From VINS

Recapture Alert! This Northern Saw-whet Owl was encountered by the VINS research team on October 17 at 10 PM. It was quickly discovered that this bird was already banded with band number 1124-47884. Our team recognized the number as one belonging to our friends up at North Branch Nature Center in Montpelier. A quick message confirmed that this bird was in fact one of theirs. The bird was originally banded at North Branch on October 11 at 8:40 PM. The bird weighed 92 grams and was recorded as a Second Year Female. By the time it made its way approximately 45 miles south, she weighed 81 grams.

Recaptures like this illustrate the importance of having multiple stations utilizing the standardized protocol of Project Owlnet. Each recapture provides important migration data and helps to better understand this secretive species.

This bird was handled for the purpose of scientific research under a federally authorized Bird Banding Permit issued by the U.S. Geological Survey and in accordance with all state permitting requirements

UV light to check age by looking at molt patterns (new feathers are bright pink) Read about this more here.

Weights and measurements determine sex

.

.Project Owlnet sounds like a Hoot.

Or a CIA dark program keeping us safe from reptilians.

I’m gonna go with a hoot.

It does sound like a hoot! It’s a bit frustrating that it’s a bit of a challenge to get involved in this stuff. For someone that isn’t already in a related occupation that would like to do some part time weekend stuff and that’s all, it seems difficult to legally get involved with anything handling wild animals. I’m sure it’s for the best, but it deters me from having a more active role in things.

Thankfully since the reptilians are still enemies of society, I can still fight them as time allows!

The bird weighed 92 grams and was recorded as a Second Year Female. By the time it made its way approximately 45 miles south, she weighed 81 grams.

She’s adorable! Is that weight loss normal? That’s, like, a 13% loss. Do Saw Whets migrate?

Do Saw Whets migrate?

Saw Whets have pretty interesting migrations. They are a migratory species, though that was discovered only in the early 1900s, as they migrate only at night, and are pretty darn hard to see to begin with. This is one of the reasons banding can provide so much information to scientists. Here is a great article about the discovery of their migration.

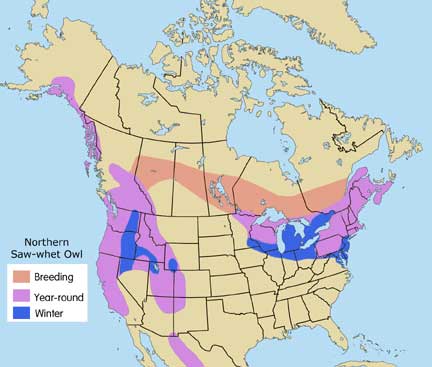

Here is a decent map of the areas that they inhabit and migrate to:

They don’t have set migration patterns, such as from Point A to Point B every season. They just kind of move to lower elevations or just south enough to get to where they find it comfortable. They are well adapted to cold though, so they can still breed farther north than most other birds if they want. Our vultures in North America do much the same. They migrate south enough to where they’re finding enough food and call that good enough.

Every 4 years though, there is what is called an “irruption” in migration. Here is a quick general article on irruptions that includes a bit about the Saw Whets. It looks to revolve around a cyclical process in rodent populations.

This article has some numerical data about migration numbers, counts by gender, and influence of the lunar cycle on migration.

She’s adorable!

I know I saw just about every owl is one of my favorites, but the Saw Whet is a little special. This post shared a great compilation image showing a random sampling of Saw Whets. They have such a great diversity of coloration and patterns. It feels like they are special snowflakes, no 2 are alike. As much as I love all the owls, I’d usually be hard pressed to tell 2 of the same species apart much of the time. That really makes them stand out to me, especially among the many little brown owls that I often feel even different species look too similar even if they are rather different in many ways.

They also have huge personalities that are far bigger than their diminutive size. Don’t tell them they aren’t ferocious hunting machines!

Is that weight loss normal? That’s, like, a 13% loss.

Normal SW weight is 70-120g for females and 70-85g for males. The page I grabbed that from says that’s 1 average lemon for a male and 1-2 for a female for reference. Average daily migration is 6.5 miles / 10.5 km, and they will take a weeklong layover when required to stock up on those important calories.

I found this study of Saw Whets from 1980 at Prince Edward Island, and they were finding a loss of roughly 0.3 grams per hour for the owl recaught within a 24 hour period. The one in today’s post must have eaten since the first catch, as the calculation would have it down about 43 grams.

Recaptured owls showed weight changes between capture and recapture. Some 63% lost weight, 29% gained and 8% showed no change. Among birds recaptured within 30 h of the original captures, (i.e., on the same or succeeding night), 73 had lost weight. There was a strong positive correlation between weight loss and number of hours between capture and recapture (R = 0.611, P < 0.001) for those birds which had lost weight, approximately 0.3 g/h. Birds caught more than 30 h later showed a less consistent pattern, but this is expected since these birds are more likely to have eaten in the intervening time.

That’s the only actual numerical data I was able to find. This news article talks about weight numbers some more with their local banding station, but it’s more general. Nice article though!

I got ticked last night. The algorithm actually recommended me something good. It was about a dozen pics from a Saw Whet banding station and had lots with their little butts sticking out of tomato paste cans that they use to transport them from the nets to the station, but the page refreshed and now I can’t find it again. I was looking forward to sharing them with you all! Hopefully I will find more.

I hope that answered many of your questions, and if I’m really lucky, will have given you more questions to ask about. Owls are really amazing!

What did Lil bro do 🙏🙏🙏

Lil Lady flew into the mist net for a second time and was subject to an alien abduction where she had her data recorded!

Some of these owls are from very far north and deep in the woods where they may have literally never seen a human before. It’s got to be a wild experience!

Owls are so cool. As a dad I’m not often up late enough anymore to hear them, but I sometimes get lucky around 5 or 6am on my way to work.

Several years ago I had found a dead Great Horned in my neighborhood. We had a wind storm the night before and I don’t know whether he died naturally or got whacked by a branch. The only real damage I could see was a single dented eyeball. The ground was too frozen to bury it, so I put it beneath a large mound of leaves and took a single feather from the ground as a keepsake, which has been protuding from a small clay pot on my bookshelf since. It was neat to actually touch my favorite owl, but obviously a bummer that it was dead when it happened.

It is not the most pleasant way to get to do it, but handling samples is the only way I’ve gotten to actually touch owl parts. Though I did get to hold a live screech owl this year, you hardly feel anything due to them being so small and the heavy leather glove. I’ve learned so much by actually getting to touch the bones and feathers though. Reading about them is one thing, but handling them is quite eye opening. Very lucky to get your hands on the feather, but keep in mind it is technically illegal, and the penalty is something that is meant to deter traffickers, so it is pretty severe potentially. I’m not saying I wouldn’t have done the same if given the opportunity, just a heads up if you aren’t aware.

Handling feathers though really taught me about how they can fly so silently. Seeing the anti-turbulance fringed edge, the long length, but low barb density, the give of the barbs themselves. It feels and looks so different than almost any other bird. If you get your hands on any other feathers, even backyard birds, compare the 2 and pick out all the differences and it should be very informative.

Oh, shit. I had no idea.

Yes, it’s a violation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. It’s got some wild penalty of like $100,000 and jail time. In your case this seems excessive, and if for whatever mysterious reason you got “caught,” I imagine it would just get confiscated. It’s not intended to harass someone picking up a random feather, and I’m not aware of any time it has been used that way.

The simple reason for it, is that instead of the feds having to take every person with a bird part to court and prove guilt, this shifts the responsibility of proof to the feather holder.

Again, this may still sound very overkill. But this is who this law is for:

Man to plead guilty in ‘killing spree’ of eagles and other birds for feathers prized by tribes

A Washington state man accused of helping kill more than 3,000 birds- including eagles on a Montana Indian reservation -then illegally selling their carcasses and feathers intends to plead guilty to illegal wildlife trafficking and other criminal charges, court documents show.

Federal prosecutors say Travis John Branson and others killed about 3,600 birds during a yearslong “killing spree” on the Flathead Indian Reservation and elsewhere. Feathers and other parts of eagles and other birds are highly prized among many Native American tribes for use in sacred ceremonies and during powwows.

Illegal shootings are a leading cause of golden eagle deaths, according to a recent government study.

Immature golden eagle feathers are especially valued among tribes, and a tail set from one of the birds can sell for several hundred dollars, according to details disclosed during a separate trafficking case in South Dakota last year in which a Montana man was sentenced to three years in prison.

The idea is to make it so nobody wants to do anything even questionable if they are killing endangered species for money. Even with this high penalty, there are still many reports of people breaking the law. So while your one feather is technically illegal, neither you nor the government want to waste each other’s time and money, so it serves as a deterrent to if someone offers you money for that feather and giving you or someone else the idea of going out and “finding a few more that were already dead when they got there.”

So I don’t want you to get paranoid or anything, I just want you to be informed. It’s a small momento of something you innocently experienced, and I would likely have done the same as you. Just keep it in mind with what company you share the story with, because while probably over 99% of stuff is acquired by random chance, a few motivated individuals can really hurt a local ecosystem, as predators reproduce in small numbers compared to most things.

If you decide to do more reading, check out how Native Americans aquire Eagle feathers. The bodies and fearhers have to all get DNA sequenced and cataloged with the federal government, and each feather has a serial number and chain of custody. Eagles are treated with the most seriousness! Even zoo/rescue eagles that die of natural causes have to be sent to DC. Amazing legal stuff!

I wrote all that and then noticed you are on the Canada instance!

The Treaty actually looks to have been made between England, on behalf of Canada, and the United States, so I’m not sure on the penalty side, but the possession is still illegal, and I also saw it stated you cannot dispose of a dead bird either, much like I said about the eagles. I guess that’s too close to disposing of potential evidence.

I greatly appreciate the information! Thank you.