Oppenheimer and the resurgence of Blu-ray and DVDs: How to stop your films and music from disappearing

In an era where many films and albums are stored in the cloud, “streaming anxiety” is making people buy more DVDs and records – as younger digital generations fear having their life histories erased.

C

Christopher Nolan has achieved some great feats of cinema in his career – but last November he pulled off something impressive on the smaller screen, too. Deep into the streaming era, where physical media can sometimes feel like a distant memory, the Blu-ray home video release of Nolan’s Oppenheimer – one of 2023’s biggest box office success stories – sparked a buying frenzy.

More like this:

- The 20 best films of 2023

- Why Disney has had an awful centenary year

- The 18 best TV shows of 2023

The 4K Ultra HD version of Oppenheimer sold out in its first week at major retailers, including Amazon. Universal released a statement saying they were working to replenish stock as quickly as possible. Some limited edition copies were fetching more than $200 on eBay. It was a sign that, for some people at least, nothing beats that feeling of holding a copy of something you love in your hand or seeing it on your shelf.

Perhaps it’s not that surprising. If anyone can inspire fervour over a release – in any format – it’s Nolan, and the DVD and Blu-ray release includes three hours of bonus footage. Then there’s the fact that, prior to its release, Nolan himself encouraged fans to embrace “a version you can buy and own at home and put on a shelf so no evil streaming service can come steal it from you”.

There is a danger these days that if things only exist in the streaming version, they do get taken down. They come and go – Christopher Nolan

Nolan explained his stance further in an interview with the Washington Post, saying: “There is a danger these days that if things only exist in the streaming version, they do get taken down. They come and go – as do broadcast versions of films, so my films will play on HBO or whatever, they’ll come and go. But the home video version is the thing that can always be there, so people can always access it.”

Other directors have chimed in to sing the praises of physical media. James Cameron told Variety: “The streamers are denying us any access whatsoever to certain films. And I think people are responding with their natural reaction, which is ‘I’m going to buy it, and I’m going to watch it any time I want.’”

Guillermo del Toro posted on X that “If you own a great 4K HD, Blu-ray, DVD etc etc of a film or films you love… you are the custodian of those films for generations to come.” His tweet prompted people to reply, sharing evidence of their vast DVD collections.

DVDs had their heyday in the early 2000s. The biggest-selling DVD of all time, Finding Nemo, was released in 2003 and shifted 38,800,000 copies. But sales have been on a steady decline since the mid-2000s. According to CNBC, US DVD sales declined by 86% between 2006 and 2019. Figures from the Motion Picture Association (MPAA) show that the international physical home entertainment market fell 16% from 2020 to 2021, while the digital market grew by 24% – and in 2021, physical media accounted for just 8% of the US entertainment market, or $2.8bn. US retailer Best Buy is phasing out DVD sales in early 2024, while Netflix finally closed their DVD rental service in 2023.

Keeping it real

And yet, not only are there many people hanging onto their existing DVDs – there’s a committed number still buying them. “Home entertainment is resurgent globally, and the factors of influence can change each year, through new tech, pandemics, pipeline and slate,” Louise Kean-Wood from the British Association for Screen Entertainment (BASE) tells BBC Culture. “But the future of physical is important to fandom, especially for 4K and Blu-ray – collectors and film and TV fans love the ownership and event of physical.” It’s not just older generations clinging onto the past, either. According to the MPAA, it’s those aged 25 to 39 who are the most likely to watch DVDs.

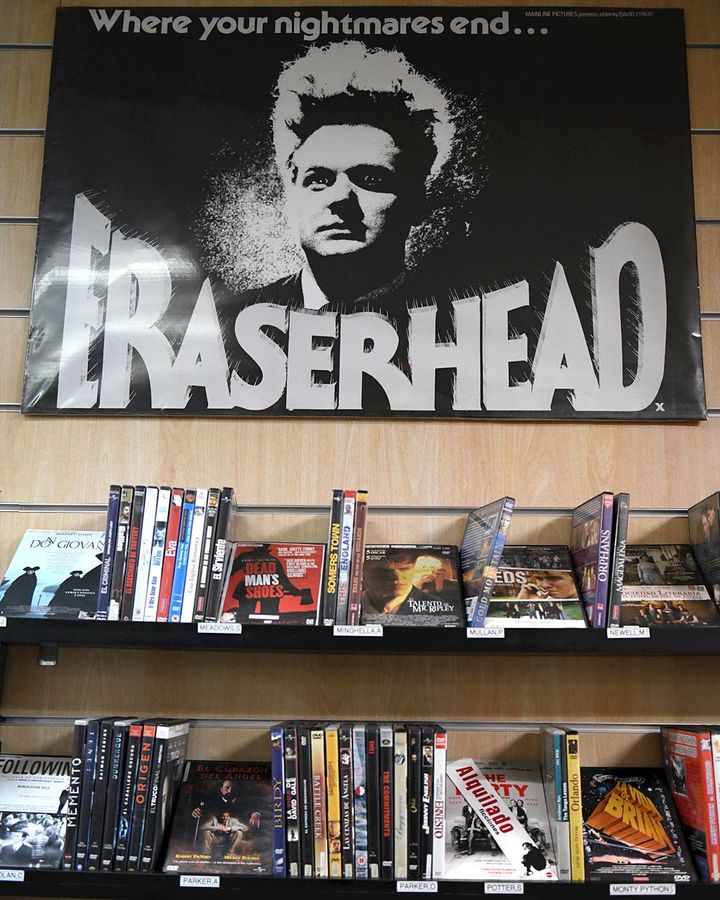

There will always be fans who want to own everything they can by a favourite artist or director, but another factor is an increasing fear over how much – or rather, how little – control we have over the content we stream. With so many streaming services at our fingertips, it’s easy to assume that we can watch any film we want, any time we want, subscription depending. But there are many films that don’t seem to exist online. In the UK, you won’t find David Lynch’s seminal debut Eraserhead available to stream. In the US, one New York Times writer recently told of her difficulty in trying to watch her favourite childhood movie, Britney Spears’ Crossroads. Nineties pop fans wanting to indulge in a spot of nostalgia with Spice World will struggle to find it in the US.

Even films that are available could disappear at any moment, as streaming services reevaluate their content libraries or remove titles due to licensing agreements. And when you pay to purchase a digital version of a film or TV show, as opposed to renting it or watching it via a streaming subscription, you still don’t “own” it – you’ve just purchased a licence to watch it. And, of course, when everything is on the cloud, we are at the mercy of a stable internet connection.

It was a problem that the film collector Lucas Henkel kept encountering. “I realised that many of the movies I enjoy are not really available on streaming services, or they disappear frequently, so the only way to see them reliably is through physical media,” he tells BBC Culture. So Henkel decided to set up his own boutique home entertainment distribution label, Celluloid Dreams. “As a collector myself, it has a lot to do with the desire to own something tangible,” says Henkel, explaining his own commitment to physical media. “More importantly, it guarantees access. I can pull out a 20-year old DVD and play it any day I want. No restrictions, no extra fees, no subscriptions… just insert the disc and press play. Seriously, what’s not to like about that? And no streaming service can match the quality of a presentation coming from a physical medium.”

Placing a premium

The company is starting with a focus on Italian thrillers – know as gialli* – *with the first title release Giuliano Carnimeo’s 1972 film The Case of the Bloody Iris. The plan is to expand to other genres in the future. “The baseline for us is that it has to be a movie we personally enjoy and that we feel deserves a larger audience.” Films will be reproduced as close to their original theatrical presentations as possible, and released in 4K UHD and Blu-ray formats. “We want to give these films the love they deserve,” says Henkel.

Celluloid Dreams will join others – most notably The Criterion Collection – who focus on curating a collection of lost classics or cult favourites and releasing them in sumptuous special editions, often with bonus material. This reflects a wider trend in sales of physical media as they shift from mass market to premium collectors’ items.

“While it’s true that physical media continues to decline as consumers embrace digital formats, we do see high-profile theatrical new releases benefiting from premium physical formats,” says Amy Jo Smith, president and CEO of DEG: The Digital Entertainment Group in the US. “4K UHD Blu-ray, which provides the highest quality home viewing in the market, experienced 20 percent growth for the full year 2022, driven by the year’s biggest titles overall, including The Batman and Top Gun: Maverick.”

HMV’s head of film and TV, John Delaney, confirms that those buying physical discs are opting for a higher quality experience. “With Oppenheimer, over 60% of our sales came from the 4K & Blu-ray versions, with most customers wanting the more cinematic experience those formats provide at home,” he says.

This shift to a more high-end experience has already happened with vinyl, which – despite commanding steep prices – has seen a huge resurgence in recent years – so much so that in 2022 vinyl sales overtook CDs in the US for the first time since 1987. And in 2023, sales of vinyl in the UK reached their highest level since 1990. CDs – once the shiny new kid on the home entertainment block – have been slowly declining for many years. Yet there have even been glimmers that even they might be having a revival, driven partly by fans buying them from merch tables at concerts, as well as artists like Taylor Swift and BLACKPINK releasing multiple collectible editions of their albums on CD.

Your DVD collection, your book collection, what you hang on your wall, the clothes you wear, all of these things are signalling to people about your tastes, your attitudes – Professor Nick Neave

The reality is though, that most CDs and DVDs already on our shelves are now fairly worthless – even some charity shops won’t accept them anymore. So why do many of us have such a desire to hold onto them? “Possessions are incredibly important for humans and this has been the case for recorded history,” says Professor Nick Neave from the department of psychology at Northumbria University. “When people are digging up Bronze Age burial mounds, they’re finding that people have been buried with small personal items. It’s really clear that objects mean a great deal to people and they imbue them with a huge amount of emotional significance.”

The things we collect – and display to others – are an extension our personality, says Neave. “Your DVD collection, your book collection, what you hang on your wall, the clothes you wear, all of these things are signalling to people about your tastes, your attitudes, your membership of certain groups.” That desire to show off what we’re into (and hopefully impress others in the process) hasn’t gone away – hence the popularity of website Letterboxd, where users list and rate the movies they’ve seen, and the flurry of Spotify Wrapped Instagram posts every December.

Neave, who is also the director of a hoarding research group, says our emotional attachment to objects means it can be incredibly difficult to let go of our possessions. “For most people, we surround ourselves with a certain amount of possessions that give us a sense of security, a sense of self-esteem, and yes, to show off our personality to visitors.”

Cloud anxiety

Younger generations, who have grown up accessing and storing everything online – especially photos – are more likely to be digital hoarders than physical ones, but with this comes an increasing level of anxiety. “It’s fairly unlikely that even if we get burgled somebody’s going to nick all of our records,” says Neave. “But if somebody hacks you, then all of your digital files could be gone forever. There’s a real terror among young people about having their entire life history erased.” He thinks this unease over everything being online could be driving some of the recent trends for Gen Z embracing physical mediums like film cameras, paper diaries and even cassette tapes.

There’s another kind of anxiety that comes from the digital world: too many options. “In our work with digital hoarding we look at how digital overload can lead to anxiety in students,” says Neave. “They feel absolutely overwhelmed with information and choice. Some people find that if you’ve got too many things to choose from, you essentially just give up.”

Algorithms have been designed to serve us options, but can end up flattening our cultural experience, feeding us more of the same that we’ve already consumed. There are signs young people are turning away from paid music subscription services. A cost of living crisis is a likely explanation – but some users also want a more meaningful, curated and intentional kind of listening experience, one where they’re not constantly hitting skip. Making the effort to pick out a CD, record or cassette, put it in the stereo and press play involves some agency – rather than just passively listening to suggested playlists. Then there’s the ethical dilemma, with increasing awareness of how little musicians themselves make from streaming services.

Whether these ripples of dissatisfaction over streaming will translate into a more significant reprieve for physical media, or are just a blip on the way to total digital dominance, is uncertain. But if you’re refusing to get rid of the stacks of CDs and DVDs in your home – or if you put the Oppenheimer Blu-ray on your Christmas list – then you can be assured that you’re not alone.

“Personal possessions are so deep rooted in our being and give us such immense comfort that I don’t think they’ll ever be a stage when everything goes virtual,” says Neave. “We’ll always want something physical, tangible and permanent.”

Films like Oppenheimer are in no danger. But there’s all kinds of things lost to the ravages of time or legal issues (Dogma being a famous example there)

Really, movie streaming shouldn’t have exclusivity outside the first year or two. Older movies should be on everything, and they just get paid a bit of the subscription money per view.

I don’t know if you heard but Paramount+ isn’t doing well financially apparently. So to make some money, they removed the Star Trek films from their US library and licensed then to HBO Max! That’s right, you can’t watch Paramount’s own Star Trek franchise on their own streaming platform. Ridiculous.