What sorcery would that require?

Blue raspberry flavor is supposed to replicate the flavor of a whitebark raspberry which is actually blue when ripe. So there are technically “blue raspberries” already. I’ve never seen them for sale or had them to know how close they are to the fake flavor, tho.

Marionberries too which are a cross of two blackberry strains.

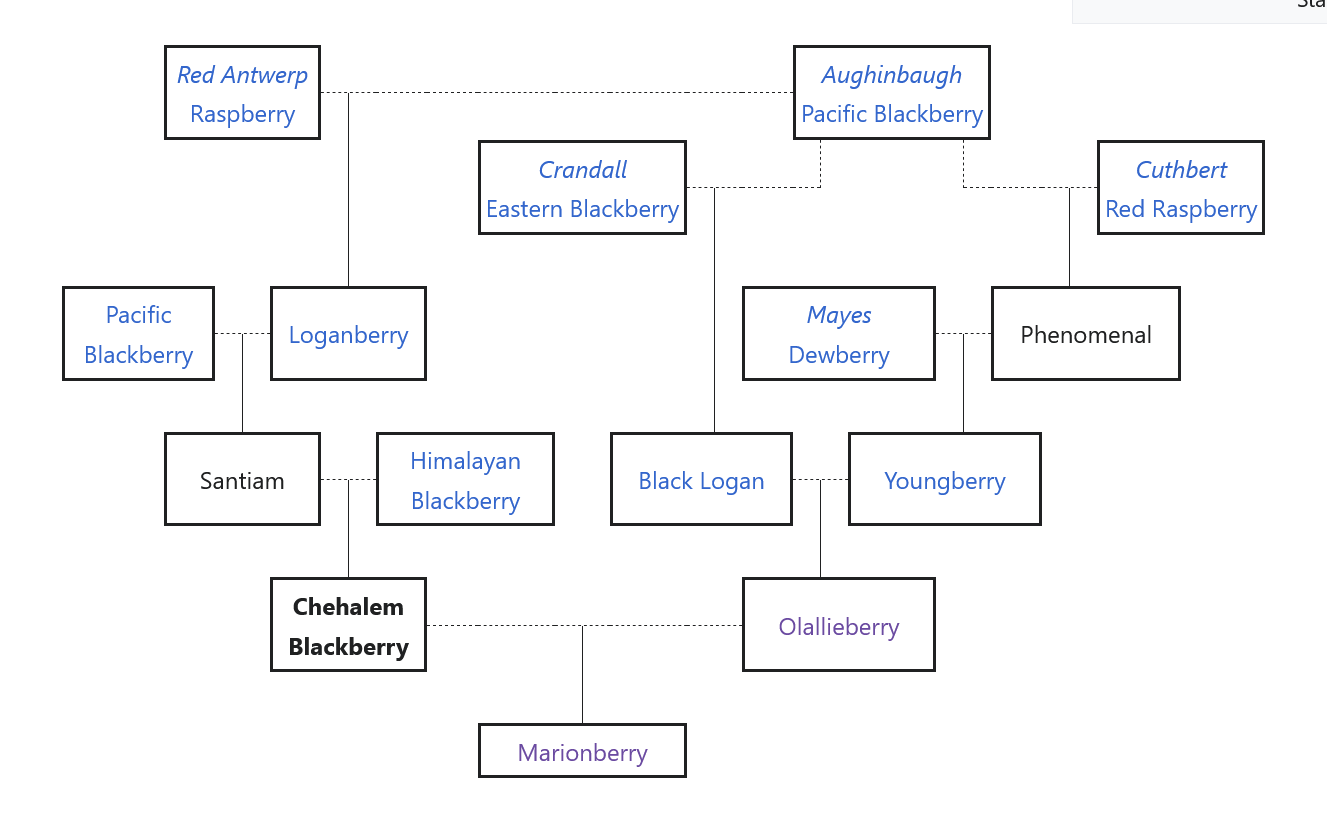

Marionberries have a very complicated lineage.

How they just didn’t stop at “Phenomenal”, I’ll never know. :)

Still not enough blue…

I had never heard that before. I might have to take a drive up north next year.

Photo:

not blue enough…

They gots tah be basically Electric Blue, like the KoolAid

The pictures of them on Wikipedia look kinda like blackberries. They’re described as being “dark indigo”

We’ve genetically engineered other colored foods before, like golden rice.

We’ve genetically-engineered many bioluminescent plants and animals.

kagis

We’ve genetically-engineered blue flowers:

We all think we’ve seen blue flowers before. And in some cases, it’s true. But according to the Royal Horticultural Society’s color scale—the gold standard for flowers—most “blues” are really violet or purple. Florists and gardeners are forever on the lookout for new colors and varieties of plants, however, but making popular ornamental and cut flowers, like roses, vibrant blue has proved quite difficult. “We’ve all been trying to do this for a long time and it’s never worked perfectly,” says Thomas Colquhoun, a plant biotechnologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville who was not involved with the work.

True blue requires complex chemistry. Anthocyanins—pigment molecules in the petals, stem, and fruit—consist of rings that cause a flower to turn red, purple, or blue, depending on what sugars or other groups of atoms are attached. Conditions inside the plant cell also matter. So just transplanting an anthocyanin from a blue flower like a delphinium didn’t really work.

Naonobu Noda, a plant biologist at the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization in Tsukuba, Japan, tackled this problem by first putting a gene from a bluish flower called the Canterbury bell into a chrysanthemum. The gene’s protein modified the chrysanthemum’s anthocyanin to make the bloom appear purple instead of reddish. To get closer to blue, Noda and his colleagues then added a second gene, this one from the blue-flowering butterfly pea. This gene’s protein adds a sugar molecule to the anthocyanin. The scientists thought they would need to add a third gene, but the chrysanthemum flowers were blue with just the two genes, they report today in Science Advances.

“That allowed them to get the best blue they could obtain,” says Neil Anderson, a horticultural scientist at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul who was not involved with the work.

Chemical analyses showed that the blue color came about in just two steps because the chrysanthemums already had a colorless component that interacted with the modified anthocyanin to create the blue color. “It was a stroke of luck,” Colquhoun says. Until now, researchers had thought it would take many more genes to make a flower blue, Nakayama adds.

The next step for Noda and his colleagues is to make blue chrysanthemums that can’t reproduce and spread into the environment, making it possible to commercialize the transgenic flower. But that approach could spell trouble in some parts of the world. “As long as GMO [genetically modified organism] continues to be a problem in Europe, blue [flowers] face a difficult economic future,” predicts Ronald Koes, a plant molecular biologist at the University of Amsterdam who was not involved with the work. But others think this new blue flower will prevail. “It’s certainly an advance for the retail florist,” Anderson says. “It would have a lot of market value worldwide.”

I imagine that it’s quite possibly within the realm of what we could do.

Interesting read and reminds me that for centuries Dutch tulip growers have tried and still are trying to create a true Black Tulip.

Thanks.

I’ve definitely seen 1